I understood long ago that what separates human beings from all other creatures on the planet is our ability to reason. Our basic animal instincts— fear, compassion, lust, pity, envy, joy, dread, etc—become harnessed and channeled through the awareness that comes from reason and that is what shapes who we are and what we can be.

I understood long ago that what separates human beings from all other creatures on the planet is our ability to reason. Our basic animal instincts— fear, compassion, lust, pity, envy, joy, dread, etc—become harnessed and channeled through the awareness that comes from reason and that is what shapes who we are and what we can be.

Wouldn’t it be nice if Paul Thomas Anderson’s new movie The Master was that simple.

There’s never anything simple about Anderson’s films, but The Master is perhaps the most oblique of them all. After simmering with it in my head for a couple of days, I still can’t come around to a way of communicating concretely about this film. While it would be easy to just write it off as a film that presents a character that seems to be a likeness of L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology and shows the workings of a fledgling cult-like religion also akin to Scientology, that’s not what this movie is about. Or at least, that’s not what the experience of this film is.

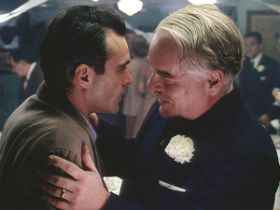

The experience of The Master comes through the total immersion into the lives and minds of two characters. One, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, has ideas of how to harness our human capacity for awareness to achieve a perfect state of understanding. The other, played by Joaquin Phoenix, is a disciple of Hoffman’s character and becomes the ideal—and willing—test subject for his theories.

Beyond this simple framework is a film rich with interpretative material—just like any religion or philosophy, or even poetry, what it’s trying to say is exactly what you think it’s trying to say. So any critic who thinks they can sum up the themes or messages in this movie will be wrong.

What can’t be looked at obliquely here though are the concrete elements of filmmaking that aren’t left open to interpretation: the acting, the writing and the direction, which are all phenomenal. Phoenix inhabits his character completely, physically and emotionally pushing the boundaries of performance. He is disturbing, haunting and hypnotic—you can’t take your eyes off him no matter how much you want to. It is clear that Anderson often just set the camera and let Phoenix go—no matter how many takes there may have been for a scene, you just get the feeling each was unique—Phoenix feels wild and off the hinges at every moment, which generates a sense of danger and excitement in each moment. Hoffman, on the other hand, is the picture of control, in being and in body, and his contrast to Phoenix—and their perfection on screen together—is the center of this film and the reason to see it.

Again, it’s really hard to narrow The Master down to some easily digestible descriptive morsel. There is a lot there and if you like movies that are challenging and wander outside the lines, you’ll get everything you want to get out of it. Anderson shot the film in 70mm and even though there aren’t the wide vistas and gorgeous landscape shots as there were in Anderson’s last film There Will Be Blood, the shot selection and cinematography are just as rich. But it is Phoenix’s disturbingly fascinating performance that stands out, even from a script with such deeply resonant themes.

While I’m not completely on board with most critics who hail this film as a masterpiece, it certainly is a finely made film by one of this generation’s finest filmmakers. And it nearly rendered me speechless, which could be the biggest testament of all.