Stephen Daldry (director) and David Hare (screenwriter) seem to have their finger on the pulse of the depressed woman. Their last collaboration, The Hours, was all about depressed women, in all different eras in fact, but all they did was mope about feeling sorry for themselves in their trapped existences. This time, however, their depressed woman does not a bit of feeling sorry for herself, and even though she is no less of a downer, her lack of self-pity makes The Reader every bit a more watchable film than The Hours ever was.

Stephen Daldry (director) and David Hare (screenwriter) seem to have their finger on the pulse of the depressed woman. Their last collaboration, The Hours, was all about depressed women, in all different eras in fact, but all they did was mope about feeling sorry for themselves in their trapped existences. This time, however, their depressed woman does not a bit of feeling sorry for herself, and even though she is no less of a downer, her lack of self-pity makes The Reader every bit a more watchable film than The Hours ever was.

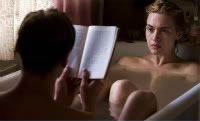

At first glance, you would think The Reader is about a boy and his coming of age, as it is a story of a sixteen-year-old who meets and has an affair with an older woman over the course of a summer, and then she mysteriously and abruptly ends things, only to reappear in his life many years later under disturbing circumstances. But The Reader is far less a story than a character study and, thankfully, is even less a boy-coming-of-age story. No, this film is seen through the eyes of Michael, the boy, and we do see Hanna, the object of his secret affair, only through his point-of-view, but it is Hanna who is the object of our obsession as well as Michael’s. As Michael is intrigued by her, so are we, as he is longing to be let in closer, as are we. Our interest follows Michael’s, as he is captivated by her mystery, her aloofness, her coldness, her distance and her moments of tenderness. He, as we do, wants to be let in further, but she retreats, and we are left even more curious—and he heartbroken. As questions are answered and secrets are revealed and we learn more and more about her, she becomes to us a fascinating character, flawed and complex, yet, for Michael, she becomes an appendage to his conscience and his soul that he must now find ways to somehow reconcile.

This film is based on a German book, is set in Germany and is filmed in Germany. There is no way to avoid it—this film feels uniquely German. There is a duality at play here, from the innate stoicism and lack of self-indulgence and self-pity of Hanna’s character, to Michael’s conscience-and-heart driven need to rectify things and to never turn his back on his past—every part of the German personality is on display here, every element of the German character is played out on screen. There are some movies that give you a real sense of place, The Reader will give you a real sense of cultural zeitgeist.

But that is to say it is still all about the portrayal of a singular character that The Reader revolves around, and that is Hanna Schmitz, played by Kate Winslet. Winslet absolutely nails this performance as she is so forceful yet withheld, and maintains such an intensity behind the lonely eyes that are truly heartbreaking. Winslet must walk a fine line here between being an idealized goddess and a monster, because at times she is each, and she must be believable as both, and that is not an easy assignment. The most difficult part here is to reveal to us a most unrevealing character, and she does so, gradually and most powerfully, and it is the best female performance I’ve seen all year.

Without Winslet’s performance, however, The Reader doesn’t really stand out from the crowd. David Kross, who plays the young Michael, is serviceable, but is so overpowered by Winslet in their scenes, it is almost distracting. Ralph Fiennes, who plays the older Michael, is, sadly, hardly used at all.

If you go to see The Reader, you would be going to see Kate Winslet and you shouldn’t be talked out of it. This is a character that they could write psychology papers about. And she nails it. When a character is so interesting that you don’t even care about the story, you just want to learn more about her—then you know you’re watching someone really good at what they do. Depressed women should all be this interesting.